Collecting, Getting Stuff Home and New Discoveries

http://vimeo.com/36865036

This video from the 2011 Philippine Biodiversity Expedition give you a good idea why the Verde Island Passage has been called ‘the center of the center of marine biodiversity’.

Researchers from the California Academy of Sciences have been visiting the Verde Island Passage area off the coast of Batangas Province on Luzon Island, Philippines for almost 20 years. Research by scientists during this period has suggested that this area may be the “center of the center” of marine biodiversity, and perhaps home to more documented species than any other marine habitat on Earth; there can be more species of soft corals at just one dive site than in all of the Caribbean.

Funded by a generous gift from Margaret and Will Hearst, the 2011 expedition was not only the most comprehensive scientific survey effort ever conducted in the Philippines, but also the largest expedition in the history of the California Academy of Sciences. Over eighty scientists from the Academy, the University of the Philippines, De La Salle University, the Philippines National Museum, and the Philippines Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources came with a mission to survey and document various aspects of the various ecosystems in the area. A further team of Academy educators attended with a mission to share the expedition’s findings with local community and conservation groups as the Expedition was happening. As part of the expedition’s shallow water team based at the renowned Club Ocellaris, Bart Shepherd, Matt Wandell and I focused upon the underwater sites that served as the inspiration for the Steinhart Aquarium in the California Academy of Sciences 212,000 gallon Philippine Coral Reef exhibit.

In part one of this series, we covered getting the the Philippines, the realities of being on an expedition and our lucky observation of hard coral spawning. In part two we’ll look at how we collected octopus and corals, how we shipped those animals back home, and more.

8 armed coconuts

http://vimeo.com/24176960

The Octopus in this video refuses to eat a crab that we generously caught for it.

In stark contrast to the beautiful obstreperous coral reefs of the Philippines, muck diving is like being on the moon. You float over seemingly endless plains of desolate grey substrate. But unlike the lunar landscape, the muck habitat is full of life; in the ‘center of the center of marine biodiversity’ the silty muck is packed with animals of all shapes and sizes. Commensal shrimp use tube anemonie tentacles for protection. Flatfish, perfectly camouflaged in plain sight, become visible only when spurred into motion by your passing. Feather Stars move their arms in slow motion, revealing their own commensal shrimp and squat lobsters hiding amongst the ‘feathers’. Venomous predators like Lionfish, Stonefish and Seagoblins hide in the muck waiting patiently for their next meal. Ambush predators like the Stargazer lie mostly buried in the silt, with only their skeletal face showing as they wait for an unlucky fish to swim over their vacuum-like mouths.

One of the major goals for the Steinhart Aquariums during the expedition was the collection of the Coconut, or Veined Octopus, Amphioctopus marginatus that inhabits these shallow muck areas. The Coconut octopus captured media attention twice in the last few years, first walking only on two legs across the bottom of the sea while looking like a coconut, and more recently, as a candidate for possible tool use due to the octopus spreading itself over coconut shell “bowls,” raising the whole assembly to amble on eight ‘stilted’ arms across the seafloor. This little octopus is plentiful in the Philippines. Furthermore, it’s personable, tenacious, and has an amusing habit of using found objects as temporary homes, making it a great display animal. Clay pots, bottles, tin cans, clam and scallop shells are all used as mobile homes for these octopus, complete with doors to close themselves in tightly and safely. These 8 armed mullusks also will defend their homes, batting away anything that comes too close; even pushing a probing finger away with surprising strength. Sometimes they extend their arms and crawl around in the muck with their temporary home on their back, as if they are transforming into snails. This octopus has never been on display before in the US, and perhaps not anywhere in the world (though it may be possible that is has been displayed in Japan) and is not available from commercial collectors, so we were very eager to collect specimens, put them on public view, and work on captive breeding behind the scenes.

It is important to mention that as a cephalopod enthusiast, I have been wanting to work with this species for well over a decade. They aren’t available in the trade, but I had been lucky enough to have observed them in the wild, and the idea of being able to work with them in captivity made giddy. So, when we entered the water around Anilo Pier just as the sun was going down I was brimming with anticipation. After 15 minutes we found no sign of octopus and I started to get depressed. This is the love hate relationship I have with muck diving – it is really like a safari because it is very possible that you will not see what you are looking for…even if it’s only a few feet away from you. When you dive to look at reefs, well, the reefs are kind of hard to miss. The muck, however, is by nature a more challenging landscape, and everything there is trying to not be seen. We kept searching. After another 15 minutes or so, we adjusted, and suddenly we saw Coconut octopus everywhere. We found sizes, as small as my thumb nail all the way to the size of a soft ball. We collected a variety of specimens and then enjoyed the dive by catching crabs and feeding them to other octopus.

There were some recreationals divers in the area looking a little lost in the dark and muck. Matt and I, flushed with success, led one one of them over to a coconut octopus that had made its home in some shells. We figured that we would catch a crab and feed the octopus so this diver could get some interesting video. We motioned for him to stay with the octopus and went searching for prey. Turns out we were gone about 10 minutes, but the diver was still where we left him. Good! His wait would be worth it. We proudly showed him the crab, and, he obligingly began to film. Of course, as you might guess, the octopus wouldn’t have anything to do with it and kept pushing it away. We shrugged our shoulders at the diver in apology and swam on.

Our Cephalopod duties complete, our focus shifted back to corals. Philippine coral reefs have long been in jeopardy due to human activities including dynamite and cyanide food fishing, overcollection for the curio trade, collection for the aquarium trade (this may only be a small percentage of the damage to Philippine coral reefs compared to other factors, but it is some of the most visible activity and thus comes under intense scrutiny) as well as a host of other impacts including development, sedimentation, run off, climate change and more. As a result, the Philippines has become very protective of their coral reef natural resources and has been working over the last several decades to make that protection more robust and more intelligent for economic and environmental reasons. All Philippine stony corals are protected by inclusion in CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) and there is currently no export of live corals from the area – unless permitted. As you can imagine those permits are not often approved. The Philippine government is interested in looking into what it would take to empower responsible and sustainable local aquaculture and mariculture efforts and granted the Steinhart Aquarium in the California Academy of Sciences CITES and Philippine permits for the export of live coral in order to help explore those efforts. On future trips to the area, The Academy hopes to present workshops on coral culturing techniques as well as coral sexual reproduction workshops as part of SECORE in order to facilitate the sustainable production of corals for research, restoration and perhaps one day to bring responsibly farmed corals to market.

Bart, Matt and I are all reef geeks, so being set loose to collect corals in an area where collection is prohibited was both a treat and a terrific responsibility. As the only public aquarium legally permitted to collect stony corals in the Philippines, the California Academy of Science wanted to obtain unique species for study, captive culture research, distribution to other institutions as well for display at the Steinhart aquarium. To support our efforts at sustainable collection building, the plan was to collect ‘found fragments’ (fragments that were naturally broken off the mother colony) of hard corals whenever possible. Fragments from larger mother colonies would be carefully harvested when there were no found fragments available. Our approach to soft corals was similar, focusing on found fragments, fragments taken from the growing margins of larger colonies, or, in the case of whip corals, taking small specimens from areas with many instances of the same coral. We tried to focus on corals that were exceptionally colored, oddly shaped, or animals generally unseen in captivity.

The trip home

With all the collecting done, the only thing left was to ship all the animals home. Luckily for us the Academy has a great relationship with an exporter in the Manila, Aquascapes Philippines Co, a company that early on embraced the idea of responsible and sustainable collection evidence by their becoming one of the first companies to be MAC certified in 2002. This relationship really streamlined our exporting process. Using their facilities meant we didn’t need to procure our own shipping boxes, shipping bags, rubber bands, oxygen, heat packs or any of the other essential supplies associated with successful shipping of live saltwater animals. They also arranged flights, getting boxes to the airport, and did all the running around to make sure all the export permits had their i’s dotted and their t’s crossed. All we had to do was arrange the stateside paperwork, state side inspections and get the animals from the collection spot to Manila.

The morning of our final pack out of the Expedition, we needed to hit the road by 9am. Since many of the researchers were not going home yet, we enlisted them to help us pack up the seemingly infinate number of live specimens we had collected. Of course we had to pack up our personal stuff and our dive gear as well, so the morning was really go go go. We swam out to the offshore holding just after dawn, disassembled it and brought all the animals to shore. There we quickly packed them up in collecting bags for the 3 hour car ride to Manila. But before we could start our ride, we had to get everything to the cars: heavy boxes of animals, and luggage heavy with wet dive gear all needed to be lugged up the 4 flights of stairs from the living area of Club Ocelaris to the road. The locals, who are short even compared to me, made the exercise look easy; they flew up the stairs with several boxes and suitcases each as we huffed and puffed with our comparably teeny loads. Finally, every tub bag and box made it to the van. After a short stop at McDonalds for a McDo (a hamburger with some sort of brown sauce on it), we were on our way to Manila.

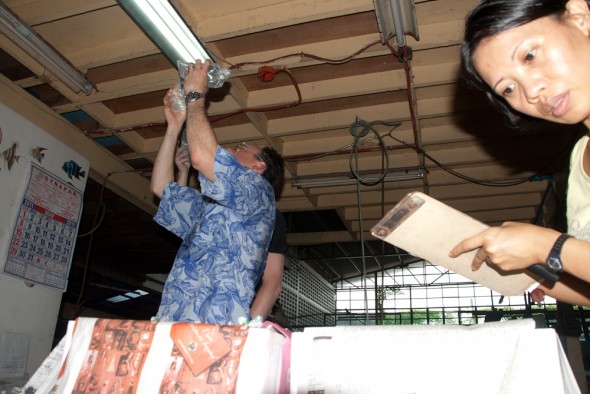

Once we arrived at Aquascapes, we sprung back into action. Since we had already packed up a shipment the week before, everyone knew the drill. The Aquascapes staff had everything ready for us including water at the right salinity and temperature as well styrofoam floats for the corals. Since they don’t normally export corals, the staff and owners of Aquascapes were very interested in what we were packing, how we packed it and why we were doing what we were doing – they took copious notes and photographs. As a huge rainstorm let loose on the city, we got into a packing rhythm – Matt and I bagged everything while sitting on tiny stools, the Aquascapes crew would seal the bags with, or without, an air gap depending on the animal, and Bart worked with the office staff to make sure everything was packed and documented correctly. Three hours later we were done and on our way to the Dusit Manila for our first real shower in 16 days, and then the the airport the next day for the flight home.

Peri’s Snake Eel

Back in the States, the researchers are still processing and classifying specimens. The estimate of species new to science discovered on the Expedition is currently between 300 and 500. That list includes sharks, fish, polychetes, nudibranchs, corals and echinoderms. Personally, the new discovery that really stands out for me involves a new species of snake eel, and it stands out because we were directly involved in its collection.

Near the beginning of the Expedition Matt, Bart and I were diving the shallows a at a site call Liag Liag, while some Academy researchers were deeper and further out on the reef slops. The site had seemingly acres of non Acropora SPS corals in 2 to 15 feet of water. Excited over collecting a Soft Coral Anemone (Heterodactyla hemprichii) we were taking in the expansive site including the incredible and visable change in water densities at the thermocline/heliocline (called a Schlieren) at about 4 feet when a lone diver appeared from deeper below us, swimming oddly. Fearing something had gone wrong the three of us made our way over to him. His hands were out in front of him and he seemed to be holding something in them. As we got closer we saw that the diver was one of the incredible local dive guides (seriously, these guys can find almost anything under water), Peri Paleracio. In Peri’s hand was some sort of eel. Not really knowing what was going on, but knowing it was important, we opened one of the large collecting bags we were carrying and carefully helped get the eel into the bag and sealed it shut. Peri was excited, and quickly returned to the depths to rejoin the group he was diving with. Because the eel was important enough to be caught by hand and brought up from deeper water, we quickly got the animal onto the boat to make sure we didn’t lose it.

Back at Club Ocellaris, as everyone oohhd and aahhd over the bucket containing the eel, the backstory unfolded. As it turns out, this was a suspected new species of Snake Eel that had been seen on a previous trip, and had actually been seen earlier in the expedition, but eluded collection. Peri had spotted it, grabbed and and knew that we had a collection bag big enough to put it in. Dr. John McCosker and Dr. Gerald Allen named the fish Peri’s Snake Eel, Myrichthys paleracia in honor of Peri for this feat of SCUBA and icthyological dexterity.

What about the fishes?

My job at the Steinhart Aquarium is pretty dreamy, and hardly a day goes by that I don’t sit back with a big grin after diving in the 212,000 gallon tank, mating cephalopods, or hearing someone on the public floor of the aquarium say something like ‘That’s a Nautilus, they’re my favorite but I’ve never seen one before’ and think ‘Wow, this is my job’. Being part of the 2011 Philippine Biodiversity Expedition was something special and hardly a moment went by – the late nights, the grueling days, or floating over rarely visited reefs – that I didn’t think ‘Wow, this is my job”. I look forward to the continued collaboration between the research and aquarium departments of the California Academy of Sciences, the chance to work with amazing animals from the Philippines, and hopefully more opportunities for me and my fellow aquarium biologists to experience the majestic Phillippine reefs in person.