2011 Philippine Biodiversity Expedition – Part 1

Planning, Science and Surreality

From Reefs Magazine

by Richard Ross

Researchers from the California Academy of Sciences have been visiting an area called the Verde Island Passage off the coast of Batangas Province on Luzon Island, Philippines for almost 20 years. Research by scientists during that period suggested that this area is the “center of the center” of marine biodiversity, and perhaps home to more documented species than any other marine habitat on Earth; there can be more species of soft corals at just one dive site in this area than in all of the Caribbean. Thus it was only natural that when the Steinhart’s 212,000 gallon reef tank was designed, the Academy decided to represent the reefs of Luzon. Ever since, Steinhart biologists have traveled to this area in small groups with the objective of acquiring first hand knowledge of the environments they hope to recreate in San Francisco.

The 2011 Philippine Biodiversity Expedition, however, was a trip of a completely different magnitude: the largest expedition in the Academy’s history covering both land and sea. Consisting of a Shallow Water team, Deep Water team and a Terrestrial/Fresh Water team, the 2011 Philippine Biodiversity expedition, funded by by a generous gift from Margaret and Will Hearst, was the most comprehensive scientific survey effort ever conducted in the Philippines. Joining the expedition were over eighty scientists from the Academy, the University of the Philippines, De La Salle University, the Philippines National Museum and the Philippines Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, as well as a team of Academy educators whose mission was to share the expedition’s findings with local community and conservation groups as the Expedition was happening.

This video by Bart Shepherd show some of the reefscapes we encountered on the 2011 Philippine Biodiversity Expedition

As part of the Shallow Water team Bart Shepherd, Matt Wandell and I surveyed and further documented the underwater sites that served as the inspiration for the Steinhart’s Philippine Coral Reef exhibit. We also responsibly collected coral, cephalopods and other invertebrates for captive propagation, research and display at our Golden Gate Park facility. As the only public aquarium permitted to collect stony corals in the Philippines, we were to obtain these unique species for study, captive culture research, distribution to other institutions as well for display at the aquarium.

Planning

On previous trips to the Philippines, Steinhart biologists had been given special permission to collect and export small numbers of small coral fragments, most of them collected as ‘found frags’. The 2011 Expedition would continue this tradition, albeit with some modifications. In order to reduce stress on the organisms, we planned to adopt Ken Nedimyer’s work with the Coral Restoration Foundation (http://www.coralrestoration.org/) to create a system for holding our coral fragments offshore until transport. We mocked up the system using materials that we could travel easily with, or that we could find in the field – silicone airline tubing, zip ties, dive weights and empty plastic water bottles as floats (after all, you can sadly find empty plastic water bottles on just about any beach in the world). The mock up went into our big reef tank for testing and was immediately dubbed ‘the coral clothesline’ by the aquariums docents.

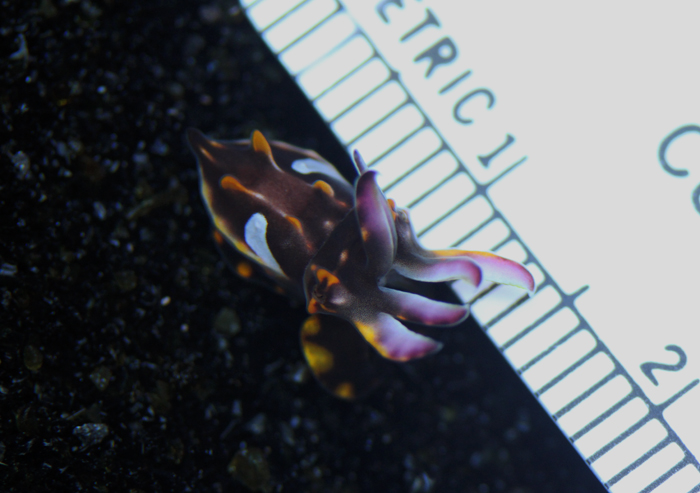

In addition to our clothesline supplies, we packed everything else we could think that we might possibly need. Some highlights: six large, low style plastic tanks that could be weighted and sunk offshore for holding larger fish and other inverts, as well as smaller plastic tanks that could be hung from the Clothesline to hold small fish and other inverts. A backpack kit for harvesting jelly gonads (as removing the gonads doesn’t impact the jellies long term and the gonads ship better than adult jellies). Fiberglass window screen to make lids for impromptu holding containers, as well as the rubber bands to hold those lids on. Dozens of tubes of super glue and rolls of duct tape. LCD microscope just in case we needed to look at something close up. Sharpies for note taking. Scissors for cutting everything. Needle nose pliers for coral fragmenting. Plastic rulers for scale in photographs. Deli cups for transport, collection and shipping or animals. All this stuff and more went into one fish shipping box and filled every empty space in our luggage.

After flying all night to Manila, all this gear, along with some very tired biologists, hit the ground running at 5am, finding our checked items, finding our ride and driving 3 hours to Club Ocellaris, a world renowned SCUBA resort, which would be the base of operations for the shallow water team.

Science was everywhere

When we arrived at Club Ocellaris, we found it had already been completely taken over by the Expedition. Science was everywhere. Across the resort, any flat space had already become some sort of makeshift lab, with equipment and apparatus piled all over the place. Every electrical outlet had a computer, camera, light or batteries charging. Containers of every conceivable kind from plastic bags, to lidded jars, to 5 gallon buckets waited everywhere to be filled with hunks of science. While all of that was exciting, we really wanted to get in the water. Within an hour of arriving our Diving Safety Officer, Elliott Jessup, got us suited up and on a boat for our first dive of the trip – we saw sea snake, corals and fish galore. After our afternoon dive, we assembled our offshore holding about 50 meters offshore so we would be ready for whatever collecting we would do the next day. When we were done, we were treated to the most spectacular sunset I have seen in a long time. Not a bad way to start off the expedition.

The overall dive plan for the Steinhart Biologists was to dive and collect for 6 days, then drive the animals we had obtained back to Manila for ship out on our ‘dry day’ (to give our bodies a chance to off gas Nitrogen in our tissues from diving), drive right back to Club Ocellaris for another 6 days of diving and collecting, then back to Manila for packing and shipping then fly home the next day. The daily schedule of activities would be a grueling marathon, but we couldn’t wait to get started.

Life in the expedition

Every morning, we woke at around 6 am for coffee and Skype video calls to home and work where it was 2 pm the previous day. Breakfast (ummm, mango shakes) and our dive briefing started at 7 am. With up to five dive boats going out each day, coming to agreement on where we would be diving was no small act of coordination. After breakfast we would collect and test our NITROX tanks for the day, get our cameras and collecting gear ready, and assemble & check our dive gear and load it onto the boats. Then we would suit up and zoom out to a good place to get under the wanter.

On each dive, we not only collected animals, but also completed multiple steps designed to track each specimen – every coral fragment was photographed and assigned a number that provided information on when it was collected, from what dive site and depth it was harvested, as well as the name of the biologist who collected it. Each coral got at tag attached to it so we would, in theory, be able to ID it later. The tagging was a learning experience and morphed over time, so much so, that next year we will most likely use heat stamped numbered zip ties as tracking id’s, but attach those zip ties to the coral with 20 gauge coated wire the tips of which are sealed with a rubberized plastic dip because the wire will be easier to manipulate and create less waste than other methods we tried.

After the second dive, we would head back to land and offload our animals. From the dock, we would change our scuba equipment for snorkels, and then swim our new specimens to the off shore holding facility, often making multiple trips. Then we would eat ravenously, then turn around and repeat the same process for the afternoon dives.

We would finally climb out of the water at 6pm for dinner… unless we were doing a night dive. On night dive days, dinner and dry-off was often as late as 10 pm.

After dinner, there was more sciencing to be done. The spreadsheet detailing what we had collected needed to be brought up to date, the Coral ID software needed to be consulted to identify each SPS coral to species. Paperwork for permits for export, and shipment/arrival details needed to be initiated and updated. When that was done, we were often drafted to help the researchers on other teams process specimens they had collected, take pictures, be all around helpful, and tend to whatever animals we were keeping onshore. Sometimes we even had a moment to geek out with Philippine scientists, or have a drink of the local rum (which I still think also contained Formalin). We were lucky if we fell into bed by 11:30.

The second night

Our first night dive was something special. The moon was full and the dive site wascalled Dead Palm. We hit the water just after the sun set to swim over stands of Acropora of all different kinds and Turbinaria colonies as large as a car. It was an SPS lover’s dream dive. About halfway through the dive the particulate in the water started to gradually become noticeably thicker, and virtually at the same time the three of us looked at each other and yelled SPAWN through our regulators.

Many corals reproduce in coordinated mass orgies where they release millions of gametes into the water. None of us had ever seen a coral spawn in the wild, and it really is as cool as it looks in the documentaries. We traced the spawn to a huge thicket of Acropora nobilis, and watched in amazement as each egg/sperm bundle emerged from the branches and floated towards the surface where fertilization takes place. Within a few days the fertilized eggs change into a coral planula, coral larvae, which swim around (yes, swim!), until they find a suitable place to settle and develop into a mature coral.

Coral spawning is one of the new frontiers in captive coral reproduction, because collecting spawn instead of coral fragments can yield many more corals in captivity in an incredibly sustainable collection method. A group of public aquarists and coral scientists formed SECORE (SExual COral REproduction – http://www.secore.org/) and they have been holding workshops in the Caribbean for the last several years to perfect spawning, fertilization and settling procedures. Building on the success of the Caribbean workshops the Steinhart Aquarium hopes to hold a SECORE workshop in the Philippines in the next few years. The most important part of such a workshop is of course timing it with the coral spawn. There is not much information on the timing of Philippine coral spawns, and none of the previous trips to the area had ever come across one, so actually observing coral spawning in the Philippines is a good and necessary start to bringing SECORE to the area.

We, along with some of the other California Academy of Sciences researchers and a Philippine television crew, returned to Dead Palm the next night where the coral spawn was in full swing yet again. We were able to find a colony of Acropora willisae when it was beginning to release gametes and set up around the coral to both collect some of the spawn and to document the event. I’ll never forget filming Matt collecting gametes in a plastic bag while the television crew was filming me film him. We were able to collect several hundred sperm and egg bundles, and though completely unprepared for the labor intensive process of fertilization and settlement, were gave it a go.

My video of the coral spawn and the gamete collection

A surreal night

After years of having the privilege of diving around the world practicing no impact diving, after collecting for the trade practicing and teaching having as little impact as possible, and after planning to take ‘found frags’ when possible, watching a scientific survey on the move takes a bit of getting used to. The researchers were collecting everything – worms, urchins, fish, nudibranchs – and just about every dive on the Expedition yielded at least one animal that seemed to be undescribed by science. The animals were being collected and preserved for scientific description, genetic analysis and as a way to be comprehensive in the survey, and being in the midst of a full on scientific survey lead to the Steinhart biologists to try to take advantage of the situation, and alter our plan regarding what we would try to bring back to San Francisco for our living collection.

On the third evening of our diving, Dr. Healy Hamilton showed us some ghost pipefish, Solenostomus cyanopterus, and some pygmy seahorses, Hippocampus bargibanti, that had been collected that day. These animals were going to be sacrificed for their genetic material. I know some people have a visceral reaction to that idea, but as Dr. Gerald Allen once said during a MACNA talk “It’s a necessary part of science”. Of course when we saw the ghost pipefish, a species that we had always wanted to work with but hadn’t because of their dismal record of surviving collection and shipping through the trade, we immediately suggested that we try to keep them alive and that we try to ship them home and put them on display – if they didn’t make it, we would still have their genetic material available for science. Though we weren’t prepared for holding these kinds of animals, Bart, Matt and I had been trained in the ultimate McGyver proving ground – the reefkeeping hobby. We got to work setting up buckets aerated by scuba tanks, faux gargonian hitching posts for the seahorses made from zip ties, and prepared ourselves to do water changes as often as needed by slogging 5 gallon buckets up and down 2 flights of stairs.

Of course, the third night of diving was also the night we collected coral spawn, so while we were preparing to try to keep these amazing fish alive, we were also preparing to attempt to keep the coral spawn healthy and fertilized which included ‘stirring’ the gametes every hour or two. This led to the most surreal night of the trip. We had coral out on the clothesline, ghost pipefish in the offshore holding tanks, trays of coral eggs and sperm, and a bucket with two pygmy seahorses next to our beds. Throughout the night we kept waking up and tending to these animals – a strange, wonderful and exhausting time.

In the end, we were successful keeping the ghost pipefish alive, and getting them home to the aquarium in Golden Gate Park. Sometime in the night we noticed that the pygmy seahorses were no longer living, and we preserved them. The coral spawn failed to thrive, and it seems that we were simply too unprepared and understaffed to have succeeded in that labor intensive realm. We learned a lot and helped move science forward. Of course, we plan that for next year’s trip, we will be much more prepared for new surprises and opportunities.

In the next installment – coral collecting, octopus wrangling, shipping & packing for the trip home, and 300-500 new species discovered.

Special thanks to Bart Shepherd, Matt Wandell and Elizabeth Palomeque