From UltraMarine

Cephalopods may very well be the coolest animals in our oceans. They are problem-solvers, can change the shape, texture and color of their skin, and are master predators. These animals have long been of interest for aquarists, but their short life spans and poorly understood husbandry needs have made them quite challenging to maintain. While keeping cephalopods is still something not to be entered into lightly, there is now a much greater understanding of their needs. In this article I’ll discuss some general concepts concerning keeping these animals, and clear up some of the common misconceptions about their care.

Fun cephalopod facts

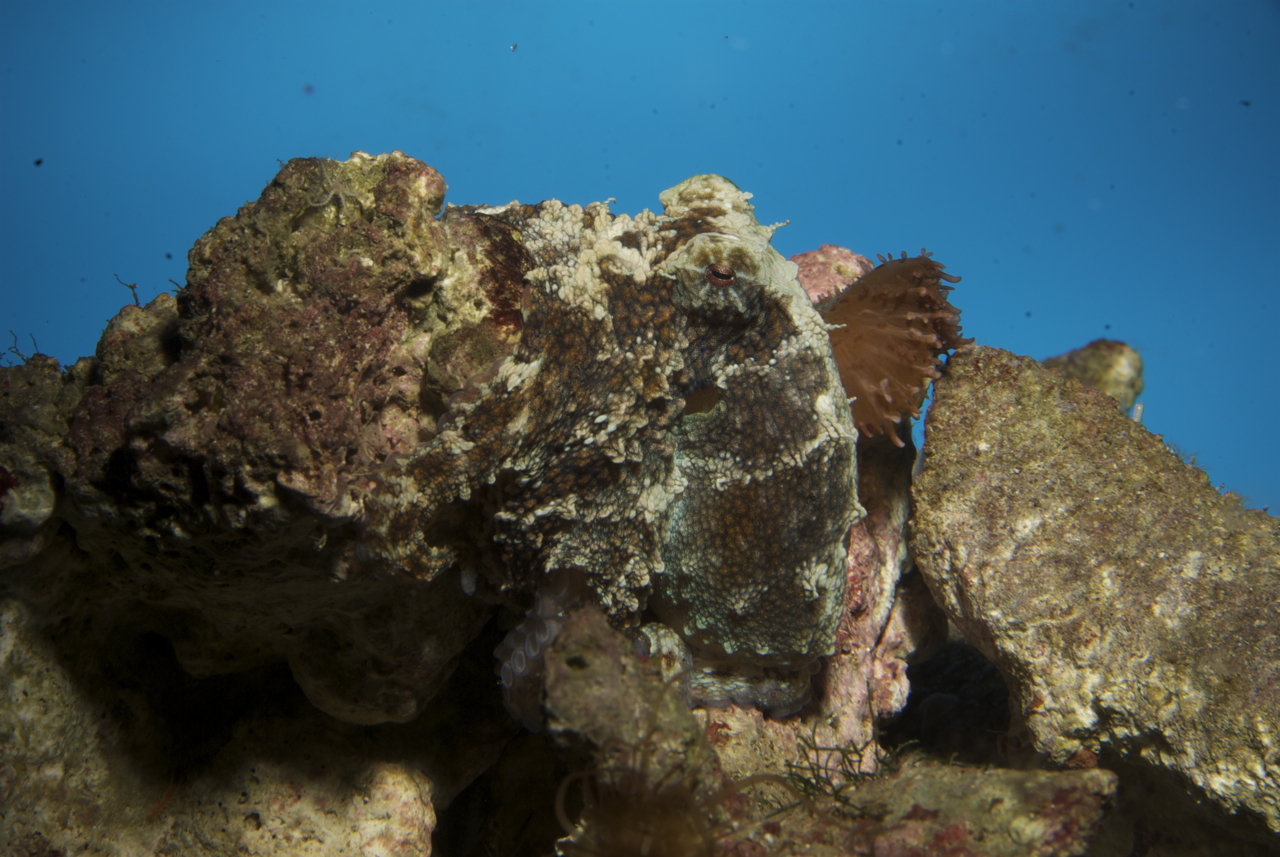

The word cephalopod comes from greek and means ‘head footed’; all of a cephalopod’s limbs come directly off its head in a ring around the mouth. Cephalopods are mollusks, related to clams and snails. There are over 1000 species of cephalopod. They occur in almost every sea, inhabiting most saltwater zones from the sand to the open ocean. Their soft flesh makes them highly desired prey, so they have become excellent at hiding, camouflage, and escape. Cephs are carnivorous, short-lived, and fast growing. Cephalopods have 3 hearts (the two extra pump blood through the gills), copper based blood, a ring shaped brain, arms and/or tentacles, a funnel for jet propulsion and respiration, generally excellent eyesight, a beak, the ability to produce and expel ink, and an ability to alter their color and skin texture providing excellent camouflage protection from predators. The plural of octopuses is octopuses, not octopi, but through common usage octopi is acceptable.

What kind of cephalopod?

The first question a new cephalopod keeper needs to answer is ‘what kind of cephalopod do I want to keep?’ There are essentially three type of cephalopods that are kept in home aquaria; Octopus, cuttlefish and Nautilus. Even determining that you want to keep one of the three is not specific enough as there are many different species that all have different requirements. Cuttlefish and octopus can be giant large, medium or small, nocturnal or diurnal, come from warm, temperate or cold water habitats, so clearly it is important to know what you are getting before you get it so you can meet the particular animals needs.

Tank Mates

Keeping cephalopods in almost any sort of community aquarium is a bad idea. Either the ceph will eat the tank mates or the tank mates will eat the ceph. Sure, if you dig around online you can find people who claim to keep cephalopods with fish, seahorses and other cephs, but the exchanges usually stop after a few weeks of reported success and are replaced with eerie silence. When tracked down, the keeper usually confides that, indeed, one of the animals ate the other.

Many corals will do well when housed with cephalopods, but be sure to avoid anything with nasty stings or sweeper tentacles. If keeping soft corals with cephalopods, be prepared deal with whatever toxins may be released from the softies by running carbon or doing water chages more often than you normally would.

Feeding

You can find many reports of aquarists feeding feeder goldfish, guppies or brine shrimp to cephalopods – none of which actually are appropriate foods. It may work for a while, but eventually, such diets lead to dead cephalopods. Freshwater guppies and goldfish don’t have the right mix of fatty and amino acids that saltwater carnivores appear to need and are often treated with copper which is deadly to cephalopods, while brine shrimp simply doesn’t provide enough nutrition.

Not all cephalopods eat the same foods. For instance, many octopus will eat animals like snails, hermit crabs, and clams, but most cuttlefish will not. Cephalopods generally eat a lot of food. To prepare for your ceph friend its important to research their feeding needs and make sure you can either collect or easily purchase appropriate foods for all their stages of life, either locally or through the mail.

Cephalopods also often need different foods during different stages of life. When cephalopods hatch they are almost always very small (Sepia bandensis can be .157in/4mm when hatched!) and will require very small, live foods. As they get bigger they will need larger and large foods to sustain them. Many newly hatched cephalopods have a hunting learning curve and may need easy to catch prey items like live mysis before they can move onto harder-to-catch foods like amphipods.

Good foods include saltwater crabs and shrimp supplemented with the occasional saltwater fish. Freshwater crustaceans can also be used as it seems their nutritional profile is very close to their saltwater counterparts. I have reared a generation of Sepia bandensis on mostly freshwater ghost shrimp. Some cephalopods, young or adult, can be trained to take thawed frozen dead foods, which means that you can feed them good quality shellfish from the grocery store or other frozen aquarium foods like mysis, silversides, or other shrimp from your local aquarium store. There are even some reliable reports of newly hatched octopus eating cyclopeeze.

There are several ways to train a ceph to take non-living food and most of them involve making the ceph think the food is still alive by gently making it move with some kind of turkey baster, pushing it with a thin acrylic rod, feeding with a feeding stick while moving the food as if it were alive, or having enough current in the tank to keep the food item moving. Mixing live and thawed food together can also help the ceph transition off of live food. Conditioning the ceph with some kind of pavlovian response can also work. Most of the time, the only reason I open the lid of my ceph tanks is to feed, and the cephalopods pretty quickly associate the lid opening with feeding and will soon strike at anything living or dead dropped into the tank. I have also gotten into the habit of tapping on the tank lid twice before I feed to let them know food is coming. Finally, there is the shrimp mobile method that seems to work very well for cuttlefish – a toothpick is tied/glued to a weighted fishing line and a shrimp, either live or thawed frozen is skewered on the toothpick and the line is hung in the tank. The current in the tank makes the food item move around and attracts the cuttle. This method also helps keep the food off the bottom of the tank where clean up animals like crabs or bristleworms can get it, plus its also fun to see cuttlefish pulling shrimp off the toothpicks.

Escape/Cephalopod proofing a tank

While it is true that some cephalopods are escape artists, some clearly are not. For instance, with its heavy shell and short thin tentacles, a Nautilus is not going to climb out of an aquarium. Similarly, a cuttlefish is also not going to climb out of an aquarium – though it is possible that cuttlefish may jump out of an aquarium though I have yet to see it happen. The most well known escape artist are the octopus, and even though some species I have kept have never made the attempt to escape, I find it prudent to assume all octopus may escape and protect the aquarium appropriately. All overflows must be covered with secured foam either glued or zip tied in place so the octopus can’t take a trip through the plumbing. The top of the tank must also be protected. I am a fan of fitting a piece of acrylic over the a portion of the top of the tank with holes cut or drilled into it to allow any wiring and plumbing to pass into the tank. The acrylic is then glued onto the top of the tank, and any gaps in the plumbing/wiring holes are plugged with epoxy putty. The remaining portion of the top of the tank can then be covered with a tight fitting piece of acrylic that can be locked or screwed into place in such a way that the octopus cannot move it to escape.

It is important to protect cephalopods from things in the tank that could hurt the animal. The intake of any powerhead or pump must be cephalopod proofed to prevent cephalopods appendages from being damaged and to prevent cephalopods from being sucked into the pump intakes. Sponge filter foam glued or held in place with plastic zip ties will usually do the trick.

Cephalopods need pristine water quality?

While water quality is a concern for all captive marine environments, the idea that cephalopods needs super crazy pristine water quality to survive seems a little over blown in my opinion. I think this idea of pristine water came about as a way to explain cephalopods not surviving long in captivity back when we didn’t have a good idea that poor handling practices during transit have disastrous effects on cephalopods. While good water quality should be the goal, I have seen many ceph keepers get over involved in chasing good numbers instead of looking for stable values. I keep cephalopods essentially the same way I keep a reef – don’t skimp on equipment, do regular water changes, and strive for stable water conditions.

Cephalopods need cold water?

This depends on species. Sepia bandensis like tropical temps from around 78F/25.5C while Sepia officinalis will prefer temperatures in the 68F/20C range. Octopus bimaculodies like cooler temps around 68C/20C or cooler while Adopus aculeatus like warmer temps around 78/25.5C. If you know what animal you are getting, you can plan for appropriate temps in your aquarium giving your ceph a better chance at a longer life.

High intensity lights will blind and kill cephalopods?

This also depends on the species. Obviously, a nocturnal animal won’t be out much while high intensity lights are on, but diurnal cephalopods should be able to take the lighting without a problem. If these animals are out and about on the reef during the midday sun, surely they can handle bright lights.

Cephalopods need large tanks?

Again, this depends on the species. A single Sepia bandensis can live well in a 30 gallon tank, while a Sepia officinalis would need something much larger in the 100-150G/378-567L range. If you are raising cephalopods from hatchlings or juveniles, you are probably going to need different size tanks/containers at different stages of life. A 1in/2.5cm or smaller cuttlefish in a 150G/567L gallon tank isn’t practical because it will get lost in such a big space. I often have a net breeder in the tank for small cuttlefish, a nursery tank for juveniles, and when they are large enough they move into the display/breeding tank. Hatchling octopus are more challenging because they need to be house in something small and escape proof like a jar with a tight fitting mesh lid.

Happily, some of the off the shelf nano aquariums can easily be modified to be octo proofed for some of the commonly available dwarf species.

Cephalopods die after breeding?

While there is some truth to this, it does not hold for all cephalopods. Most cuttlefish available to hobbyists do not die after breeding at all, instead they can spend the last half of their lives breeding and laying eggs over and over again. There are some species of octopus that can lay and brood several clutches of eggs over their lifetimes. Those that do breed only once don’t really die after breeding, rather the female will often stop eating once eggs are laid and die shortly after her eggs hatch while the males may or may not breed many times before their end.

Cephalopod ink is poisonous?

This idea came about when cephalopods shipped in bags ink during transit and are dead on arrival. While it appears that most ceph ink contains some kind of toxin, it seems that this toxin in not what killed these animals. Rather, the ink covers the gills and suffocates the animals. While an inking event in the home aquarium can be dangerous, it is something that can easily be combated by ensuring that the system is running an appropriately sized, quality protein skimmer to remove the ink from the water over a few hours (as well as helping maintain good water quality). Having activated carbon on hand can also help in clearing up inking events.

Cephalopods ship poorly?

In my opinion cephalopods got this reputation because the were poorly understood and treated badly in the chain of custody. However, if collected well and treated well, cephalopods ship just fine. Fortunately, it seems people in the chain of custody have begun to understand the shipping and husbandry needs of these animals, and are taking better care of them during transit.

Getting an animal

This can be the most frustrating aspect of ceph keeping. Cephalopods are not consistently available, and what’s worse, they are often identified incorrectly by whoever is selling them or collecting them. Often, ordering a particular species sight unseen ends means you may wind up with whatever species happens to be available instead of the one you actually want. The best way to deal with this problem is to take a photo of the ceph in question at an LFS or find a WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) website with a photo of the actual animal for sale and post that picture on the site for all things cephy, www.TONMO.com. While identifying a ceph from a photo is not always accurate, TONMO is a central hub for ceph enthusiasts and professionals, so the ID info you get there is generally pretty good. Plus, because these people live and breathe cephalopods, many are up to date on what animals are currently available (both captive bred and wild caught) where to get them, and can help answer any husbandry issues, so I consider the site an invaluable resource.

Short life span

Most tropical cephalopods live between 1 and 2 years. As it nears the end of its life span, a cephalopod can enter “senescence.” During this stage of life, the animal becomes listless, stops feeding and its overall body coordination deteriorates. The animal seems not to care about anything, sometimes not bothering to get away from normally harmless clean up crew animals like hermit crabs and bristle worms…even when those animals begin eating their living flesh. In the wild, animals going through senescence would quickly be eaten by a predator, but in a captive environment some cephalopods can go in and out of senescence for months. Thus, the reality of ceph keeping is that you don’t have much time to enjoy the animal, and the ending may not be pretty, so be prepared.

Exotics

There are a number of exotic species of ceph that have been appearing for sale with some regularity including Wunderpus photogenicus, mimic octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus) and flamboyant cuttlefish (Metasepia sp). Even experienced cephalopod keepers with mature tanks should think long and hard before obtaining these species. Their needs are resource intensive, specific, and not yet fully understood. Since these animals are almost always only available as adults they have months or weeks left to live and their impressive price tags make keeping them hard to justify. Perhaps more importantly, the size and health of their wild populations is unknown, so their collection may have very real negative impacts on the survival of the species.

Blue ring octopus (Hapalochlaena sp.) are commonly available, but in my opinion, they should be considered exotic because they are incredibly venomous. While there has never been a documented case of a hobbyist being killed by these animals, and the amount of venom varies with individual animals, ignoring the possibility of being bitten seems like a bad idea. It is possible for blue ring venom to kill an adult human in minutes, and there is no known antidote. It is pretty obvious that if you are going to keep one of these animals it is only prudent to be extra super careful octoproofing the aquarium and to strictly follow venomous animal protocols. Better yet, I would avoid the species completely.

Nautiluses are one of the most frequently improperly kept cephalopods in the hobby. Since these animals are found in tropical places like Palau, many people wrongly assume they will thrive in a tropical aquarium. During the day, nautilus dive as deep as 1500f/457m where the water temperature can be below 50F/10C and only rise to the shallower, warmer water at night. In captivity, their lives tend to be very short when kept in warm water, so if you plan to attempt to keep a nautilus plan on a chiller. Nautilus also require a large, deeper tank devoid of complicated aquascaping so they don’t jet into rocks and injure themselves or crack their shells. Interestingly, Nautilus have some of the poorest eyesight in the ceph world and their eyes are not encased in an orb or fluid, rather they are open to seawater and amount to what is essentially a pinhole camera.

With their beautiful shells and many tentacled faces, they seem like incredibly intriguing animals, but the reality is that most of the time the do little besides float in the water or hold onto the side of the tank. When they feed they are incredibly interesting, but this only lasts for a minute or two, so be prepared for this animals massive inactivity before you bring one home.

Breeding

In the last few years there have been great advances in breeding several species of cephalopods. Breeding cuttlefish is relatively straightforward, as the mating is generally not violent and males and females can be kept together, sometimes in groups, as long as the aquarium is large enough to provide sufficient space for the animals to avoid each other. Cuttlefish lay clutches of relatively large eggs, and hatch as miniature copies of adults right out of the egg. There have been some issues with the viability of eggs over successive generations.

Octopus on the other hand, are a bit more complicated. Octopus can be thought of as two groups, small egged and large egged. Small egged octopus lay small eggs that hatch out as planktonic paralarvae which stay in the water column before developing into something resembling their parents. The paralarvae are currently essentially impossible raise or feed. Large egged octos on the other hand, emerge from the egg as miniature versions of their parents, ready to feed.

When available, captive bred cephalopods make better pets than wild caught cephalopods simply because you will know their age, and therefore have a more accurate idea of how long they will live. Captive bred cephalopods are sometimes available for sale onwww.TOMNO.com.

Keeping and breeding cephalopods has been some of the most rewarding of my saltwater experiences. I hope this article clarifies some of the issues surrounding the care of these animals and inspires cephalopod keepers to do some extra research prior to purchase so that their experience can be as fulfilling as mine has been.

Resources

Cephalopods: Octopuses and Cuttlefish for the Home Aquarium by Colin Dunlop and Nancy King

Cephalopods: A World Guide by Mark Norman and Helmut Debelius

www.TONMO.com

www.DaisyHillCephFarm.org

www.TheCephalopodPage.org